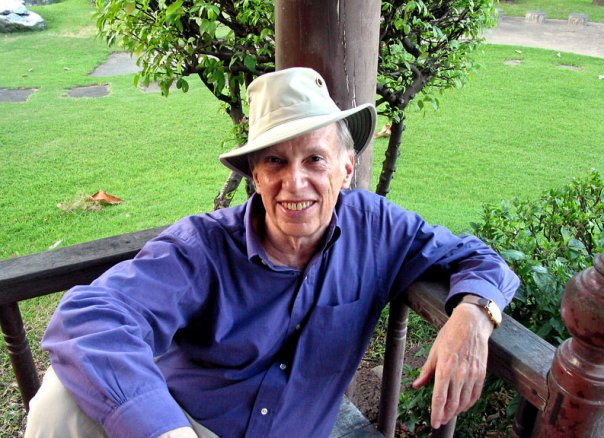

Gay Pride Day, June 1998. I was producing An Evening with Quentin Crisp in a small theatre in Greenwich Village. During that evening’s performance, Mr. Crisp had once again stated that he thought “gay pride” was silly. If you were gay, you were gay, that’s all, nothing to be proud of particularly. A member of the audience then said, “I saw you today in the gay pride parade. If you don’t believe in gay pride, why were you in the parade?” Answer: “Because Mr. Glines asked me to be.” Blunt and to the point. That was his style. But he hadn’t been quite honest. He knew the value of publicity. I mean, you don’t dye your hair purple if you want to go unnoticed.

Gay Pride Day, June 1998. I was producing An Evening with Quentin Crisp in a small theatre in Greenwich Village. During that evening’s performance, Mr. Crisp had once again stated that he thought “gay pride” was silly. If you were gay, you were gay, that’s all, nothing to be proud of particularly. A member of the audience then said, “I saw you today in the gay pride parade. If you don’t believe in gay pride, why were you in the parade?” Answer: “Because Mr. Glines asked me to be.” Blunt and to the point. That was his style. But he hadn’t been quite honest. He knew the value of publicity. I mean, you don’t dye your hair purple if you want to go unnoticed.

It was relatively easy working with Mr. Crisp. The initial negotiations involved a bit of maneuvering because like a good Asian Buddhist, he would never say “no”, not directly. He would hedge on the number of performances a week, etc. – money was negotiated with his agent – and he agreed to appear or perform only after I’d suggested what he wanted in the first place. After that it was very easy: no rehearsal; he didn’t ask for approval of the set or lighting; his only request was that he have chair with a table with a glass of water on it, a microphone, someone to walk him from his dressing room to the wings, and whiskey in the dressing room. Aye, that was the rub, the whiskey. A nip or two, he was mellow and charming, but a nip too many and he could forget where he was in the first act, which was one long monologue. Later that year, I produced An Evening in a theatre on Theatre Row, opening on his birthday, which was Christmas. It was a huge success. We were sold out almost every night, in spite of snow and bitter cold. He took sick during the run but never missed a performance, and he always arrived at the theatre on time and stayed after the performance to autograph copies of his books. But one night after a nip too many, he went dry in the first act, just stopped talking. How he got out of it, I don’t know. I was in the box office going over that evening’s take, when it happened. I can only assume the audience forgave him, thinking it was his age. And who was I to disillusion them. After all, he was a rather grand illusion to begin with.

Now to prevent Mr. Crisp’s being overly fortified with whiskey, the stage manager would try a number of tricks. For instance, he’d buy only half pint bottles so that Mr. Crisp would ration himself according to the level of the whiskey. And when the bottle was empty, the stage manager would be late in bringing him a new bottle, just 15 minutes before curtain time. Once the stage manager diluted the whiskey, but Mr. Crisp knew immediately and scolded the stage manager in severely plonking tones.

Also, over fortification would cause the first act to slow down, and the laughs wouldn’t be quite so loud and spontaneous. This is something I could judge as I’d stand at the back of the house during the last five or ten minutes of the first act. Now, the second act was simply Mr. Crisp’s answering questions from the audience, questions which were written on slips of paper during intermission, put in a basket, and delivered to the table on stage just before the lights dimmed for the second act. So if the first act had been sluggish, the staff and I would write down questions for which we knew he had brilliant answers that never failed to cause roars of laughter, and drop them in the basket. He had set answers for every possible question. For instance, question: “Should I tell my mother I’m gay.” Mr. Crisp’s answer: “Don’t tell you mother anything!”

And it was very easy to meet him. Once a young man from out of town asked me if I knew Quentin Crisp and would there be anyway possible for him to meet Mr. Crisp. I said, easy, just look him up in the phone book, call and invite him to lunch or dinner. The boy called. Mr. Crisp suggested they meet at a diner close to where he lived, then added, “I’ll be sitting in the window like a Dutch whore.”

I had met Mr. Crisp many times before I ever asked him to appear or perform for me. I remember a dinner party of about 12 people. Through cocktails and dinner he was the proverbial shrinking violet, but once the meal was finished, he bloomed like a giant sunflower, and the anecdotes poured out of him, which reminded me of Oscar Wilde, who used to try out his epigrams at dinner parties, and once he’d gotten their rhythm right, he’d put them in a play. Same with Quentin Crisp. But sometimes Mr. Crisp told things in private which he would never tell from the stage. For instance, his quote of Marlene Dietrich, “If you don’t let them fuck you, they won’t come back”.

The run of Mr. Crisp’s show on Theatre Row was the last time he appeared on stage in his adopted hometown of New York City, and it was the last thing I produced before retiring to Bangkok, Thailand. During the run a London producer wanted to produce Mr. Crisp on the West End on off nights. I thought this was a brilliant idea, and I was eager to co-produce, but when I asked Mr. Crisp about this engagement, he said, no, if he went back to England it would kill him. The last I heard of Mr. Crisp was that he had gone back to England, was performing there, and had died.

I remember on that Sunday in June, Gay Pride Day, 1998, while I walked beside the car that Mr. Crisp was riding in, one young man ran up to shake Mr. Crisp’s hand and explain that Mr. Crisp had saved his life. I knew what the boy meant. Mr. Crisp barely acknowledged him. I remember him saying only one thing as we took that long trip down Fifth Avenue, past crowds of people who cheered and applauded him — it was as we passed a mass of uniformed policemen — he said, “That’s very frightening.”

To be one’s self in spite the danger is, for me, the great lesson that Mr. Crisp taught us all. The rest is gravy.

|