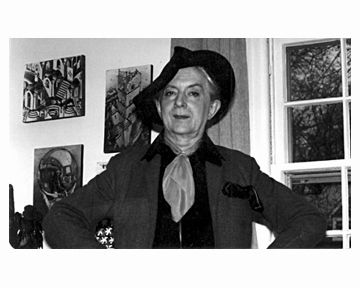

QUENTIN CRISP: THE RADICAL by David McReynolds |

|

My contact with Quentin was almost patronizing in its origin. I had seen Naked Civil Servant (before which I'd never heard of Quentin Crisp). I was deeply moved by the film, as were, I suspect, almost all who saw it. Then I saw this quaint little old man, tinted hair, elegant hat, walking by himself up Second Avenue or, on some days, down Second Avenue. I knew at once that it was Quentin Crisp. I thought to myself, "I'll bet he is old and lonely. Why don't I ask him for dinner." So I checked the phone book, found his address and wrote Mr. Crisp a letter. Then the sheer presumption of what I had done overwhelmed me. "Why do you suppose, David, that this man is lonely?" Days passed and finally, having written the letter, I phoned. "Yes?" said the voice at the other end of the line. And I explained who I was and Mr. Crisp said, "I wondered when you would call." So he agreed to come to dinner. By then I had begun to realize he was a real celebrity and so I doubted he would come, I panicked and set up a dinner party. In the end one friend, Vicki Rovere, came and the two of us hosted Quentin. I think this may have been the first time in his life he'd broken bread with political radicals. Some of his jokes were limp — as if this were new ground to him. ("Yes, but if you don't have war, how shall we get rid of all the people?") As he talked it became clear, first, that he was extremely intelligent. Second, that he was a radical, which traumatizing news Vicki and I broke to him as gently as we could. ("Oh dear, a radical? I've never thought of that.") But who else would take on all of society? Later I saw Orlando (about which Quentin and I had talked on the phone before it's release), and if I'd seen that first I'd never have had the nerve to invite him to dinner. Fortunately I acted on my first impulse and a friendship, however odd it may have seemed, was formed between a radical socialist and pacifist and Quentin Crisp. We saw a film together at least once a month. The last film we saw, before he left for England and his death, was American Beauty. Since Quentin usually liked bloody films I had a list of them at hand when I'd phoned him but he said, "I hear American Beauty is good." So we saw that. (Early in our friendship he would always say, when asked what he might want to see, "I want to see what you want to see," but as the friendship became more solid he actually became assertive enough to say what he wanted to see.) The term "effeminate" never occurred to me in dealing with Quentin. In fact, if he was at my apartment for a party and had gotten started on his second stout, he struck me more as a sailor who would have been quite at home with his foot on the bar rail. Aside from his acute intelligence, one of the things which endeared Quentin to me was that he never had a "bitchy" word to say of anyone. There were actors he thought "dreadful" but, even when I didn't agree with his judgement (on Montgomery Clift, for example), his judgement was an artistic one, not a personal feud. Yes, he never called me David. And for some time I hesitated before calling him Quentin, but the point was reached where "Mr. Crisp" seemed as impossible for me, as "David" was for him. The only time he got genuinely provoked with me involved his determination to get himself killed in traffic. He had started across Third Avenue as we went to Sony Cinema there on 10th Street, and I put a restraining hand on him to prevent his walking into a truck thundering in our direction. "Don't do that! You could have gotten me killed!" After that I walked just a bit behind him, so there would be someone alive to dial 911 if or when he got hit. Because my own life has been filled with "remarkable people," saints and felons (sometimes, up close, the "remarkable people" are irritating but more often they are . . . remarkable . . . it is just that the radicals with whom I've worked don't show up in People magazine in gossip columns), Quentin was not such a totally remarkable encounter. If I loved him it was not because he was one of the few remarkable people I've known, but because of all the remarkable people I've known, he was unique. As, I assure you, each remarkable person is. Intelligent, witty, thoughtful, and determined not to be hurtful, just as he was determined to be himself at any cost, he was a great man. Once I asked him if he would appear at a benefit for War Resisters League of which I was working on ("A Night Out of Time"). He agreed, I picked him up in a cab, got him there to a left-wing Hispanic meeting place, and he agreed to read a bit from one of his books. When he finished he got a standing ovation. Quentin turned to me and said, "Why are they all applauding?" Once more, I had to break the news to him — "Quentin," I said, "you are a radical who took on society — that is why they were standing and applauding." I rejoiced in the fact he was so politically incorrect. With all of you, I miss him. And looking back, I am so glad that on that day, some years ago now, I wrote a letter to what I had mistakenly thought was a lonely old man. |

|

David McReynolds, well-known peace activist for the War Resisters' League and former Presidential candidate for the Socialist Party USA, has written numerous articles in publications as diverse as the Progressive, Village Voice, WIN magazine, and Nonviolent Activist. He is the author of a collection of essays titled We Have Been Invaded by the 21st Century, published in 1969.

|

|

Copyright © 2005 by David McReynolds for the Quentin Crisp Archives. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Photograph copyright © by Elaine Goycoolea. All rights reserved. Used by permission.   Site Copyright © 1999–2007 by the Quentin Crisp Archives All rights reserved. |